Forget China, There’s An E-Commerce Gold Rush In Southeast Asia

There’s a myopia blinding e-commerce players to the reality of opportunities in Southeast Asia. Everyone is looking at Asian economies from under the shadow China casts on the economic landscape, which can’t help but obscure the picture.

China is one of the most developed markets in e-commerce today and with mobile commerce via WeChat, the dominance of Alipay and the entrenched online shopping behavior it is arguably more developed than Western markets.

However, businesses are, in fact, wasting their time and resources expanding into China and Southeast Asia will be the next gold rush. Here’s why:

It’s Too Late For China

- The Chinese b2c e-commerce market is saturated. Only the deepest pocketed players have a chance

In the Chinese e-commerce race the market giants have taken too large a lead for too long in China.

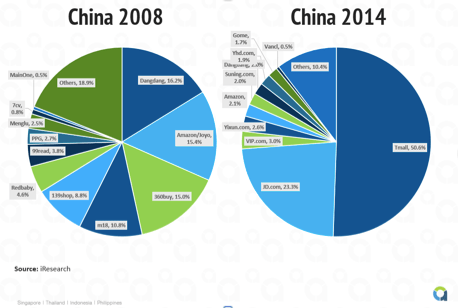

With Alibaba’s Tmall and JD dominating the business-to-consumer (B2C) space (51 percent and 23 percent of total B2C sales in China respectively) and Taobao owning over 95 percent of the consumer-to-consumer (C2C) space, only those with the long term vision (i.e. the deepest pockets) have any chance of surviving, because they can out compete anyone.

This is largely because B2C e-commerce, unlike pure tech companies, still benefits from economies of scale.

With Tmall and JD owning close to three quarters of the Chinese B2C e-commerce market, there just isn’t much room for both “smaller” global and local players like Yihaodian, Suning, Amazon and VIPShop to compete.

The sheer scale and volume that these players wield from their first mover advantage in the world’s most populous country means they enjoy efficiencies in branding and marketing through lower media costs and through word-of-mouth marketing, as well as logistics and sourcing through preferred rates and stronger bargaining power for warehousing and shipping goods nationwide.

“Smaller” players such as Amazon, Rakuten, and Neiman Marcus entering the market struggle to compete because of fewer domestic resources, a lack of understanding of the Chinese market, as well as slower execution. Recent examples include Macys and Neiman Marcus shutting down their China e-commerce initiatives and Amazon throwing in the towel and opening a store on Tmall, China’s largest B2C marketplace.

With Tmall and JD owning close to three quarters of the Chinese B2C e-commerce market, there just isn’t much room for both “smaller” global and local players like Yihaodian, Suning, Amazon and VIPShop to compete. They cannot tap into the economies of scale enjoyed by the market leaders. B2C e-commerce is a winner-takes-all market where the rich get even richer.

- Cross-border commerce is hot but its potential will dry out quickly

Plagued by food and health scandals, Chinese consumers are increasingly turning abroad in order to avoid risk of buying fake beauty products, contaminated milk powder, or fake pharmaceuticals.

Concurrently ‘cross-border e-commerce’ has popped up as the business trend du jour in China. It is a strategy that sidesteps the domestic dominance of major players and aims to not only make shopping on overseas websites seamless for users but also offers much better pricing than traditional imports.

Yihaodian states a case study of a popular brand of milk powder that ended up 40 percent cheaper via cross-border e-commerce than via traditional import.

“Cross-border is the last blue ocean for Chinese e-commerce,” Yihaodian senior manager Yang Shenling boasted confidently during her presentation at the Asia Cross-Border Conference in Shanghai last month. As one of the leading B2C websites in China, majority owned by Walmart,

Yihaodian is certainly positioned to comment on where the next big streams of revenue are going to come from. But is she right? Sadly, no, or rather, not completely.

The inbound cross-border markets is estimated to be 155 billion RMB ($25 billion) and is expected to grow to a whopping 1 trillion RMB ($164 billion) by the end of 2018, according to The China e-Business Research Center cited by Shenling. But when we asked Yihaodian how big their new cross-border business was in terms of percentage of total company sales it turned out to be only 2 percent and projected to go up to 10 percent over the next five years.

Ten percent is still a very small number. Getting there will be an uphill battle as the quality and safety of domestic products will no doubt increase over the next few years thanks to increased government pressure and regulation. As quality improves there will be no need for Chinese consumers to look abroad.

In many ways, cross-border e-commerce in China can be seen as a desperate move to cope with the fact that the domestic market is reaching saturation. And despite all the hype, it is still a very small business compared to the domestic e-commerce market.

The Next Gold Rush Is In Southeast Asia

- Unlike other markets, Southeast Asia is the only one that is raw and ready

Chinese (and global) Internet companies should look at Southeast Asian e-commerce as their next potential gold rush.

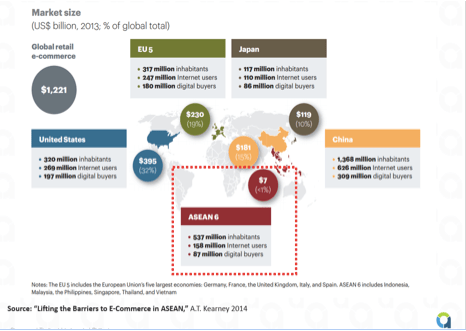

If the premise that it’s too late to dig for e-commerce gold in China is true — and India is also saturated because of the huge sums allocated by Flipkart, Snapdeal to compete, then perhaps it’s time to look elsewhere in Asia.

The paucity of payment systems in the Southeast Asian is a case in point itself. Thanks to Alibaba and WeChat, COD decreased from more than 70 percent of total payments in 2008 toless than 21 percent recently in China during last year’s Singles’ Day mega sales (think Cyber Monday / Black Friday for China).

Southeast Asia, however, doesn’t have an Alibaba or WeChat yet. Due to their size and reach, Alibaba and Tencent were able to turn their online payment methods into the de-facto standard for e-commerce in China.

Southeast Asia is still fragmented. Until local financial institutions and/or e-commerce players get their act together in terms of payment platforms, COD will remain the dominant payment methods covering over 80 percent of total payments.

- There’s no clear market winner

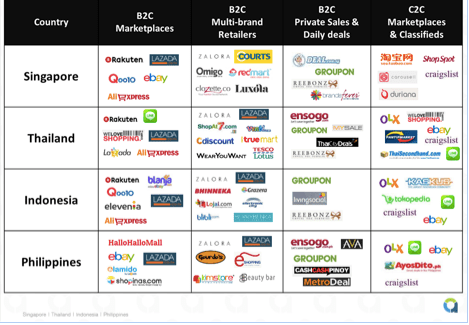

Like China in 2008, the Southeast Asian e-commerce market is still fragmented and up for grabs. True, there are players making a splash like Rocket Internet’s Lazada, estimated tohave 20 percent market share, but if China is any sort of crystal ball, that lead portends nothing.

Take sites like DangDang and Amazon for example. In 2008 they still had 16 percent and 15 percent of the Chinese B2C market, according to iResearch study 2008, but fast forward to 2014 and they have fallen off the map to 2 percent and 2.1 percent respectively in a market dominated by Tmall (51 percent) and JD.com (23 percent).

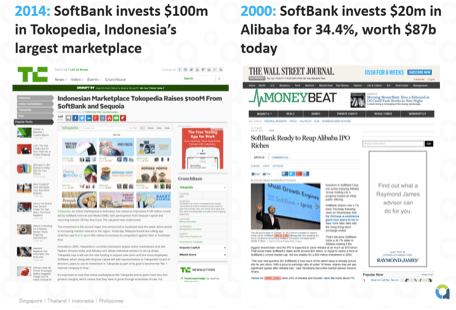

It’s still early to tell who’s going to win. Local players like MatahariMall recently raised its battle flag and committed $500 million to build the biggest e-commerce site in Indonesia. Global players like Alibaba and its $249 million SingPost investment, as well as Chinese e-tailer VIPShop through its investment in Ensogo (previously LivingSocial), are also entering the market.

Consumer-to-consumer e-commerce is also in transition. Unlike China, the C2C e-commerce space will not be dominated by one key player like Taobao. Alibaba rode China’s manufacturing and export boom which benefited Taobao, allowing the latter to grow into the C2C juggernaut it is today.

At the higher end of the C2C spectrum, players like Lazada and Tokopedia are trying to mimic the T-mall model, going after higher-end brands like L’Oreal, P&G, and Samsung.

At the lower end, incumbents such as Rakuten, Kaskus, and OLX are more like a long-tail version of Taobao or digital flea markets. Then there are new entrants like Line, the popular messaging app, which is trying to establish a foothold in the mobile marketplace domain.

Don’t be fooled into thinking that Lazada has staked any lasting claim on the market just because they have spent half a billion dollars in it. In an ecosystem this raw, Lazada’s headway plays the role of an explorer, clearing the structural overgrowth away for the future of e-commerce, rather than solidifying their position as a conqueror.

Today, Lazada’s estimated 20 percent market share may appear intimidating but remember what happened to DangDang and Amazon’s headstart in China? Anything can happen in a market as dynamic as Southeast Asia.

- Like China, Southeast Asia skipped Web 1.0, which will lead to similar hyper growth in e-commerce

Because both markets lack a quality, open long-tail publishing inventory, China’s online advertising ecosystem never developed beyond the major portals such as Sina and Sohu.

This was critical to the speed of evolution in e-commerce for China because it forced Internet companies to explore non-advertising based monetization such as Value-Added Services (VAS) and e-commerce as ways to make money.

Close to 80 percent of Tencent’s revenue today comes from VAS and e-commerce. Compare this to the U.S. where companies like Google, Facebook, and Instagram have always been advertising-first businesses. All this accelerated the growth of e-commerce in China from a supplier side.

We see something similar happening in Southeast Asia e-commerce. When the Internet started taking off in Southeast Asia (excluding Singapore), the market here was already at the very tail end of the Web 2.0 wave. Users in these markets never went through Web 1.0 or even 2.0. By the time people finally got online, social media platforms like Facebook or Instagram already dominated the market and detracted from the Web 1.0 ad revenue model (we write about SEA leapfrogging web 1.0 extensively, here).

With lack of ad money floating around online in Southeast Asia, most publishers are forced to look into other means to monetize online. In Thailand, Line’s main sources of income are selling digital stickers and brand pages — and that’s a messaging app with 60 million users. The company is also actively testing e-commerce via products such as LINE Flash Sale, LINE Hot Deal, and LINE Shop.

This pressure has had a remarkable impact on accelerating the adoption of e-commerce as a revenue stream by local players.

Déjà vu?

- Mobile e-commerce adoption will be faster in SEA than in China.

In Shanghai, Taobao Partners” help brands operate stores on Tmall, taking care of everything from marketing, merchandising, store design, as well as fulfilment and logistics. Some say they are shifting strategy away from T-mall and towards WeChat stores.

WeChat’s rise is all due to the company’s mobile commerce platform, which has completely disrupted the e-commerce space. Consumers in China can order food, book taxis, pay bills, transfer money, get their laundry done and sell products all within one single app.

Southeast Asia’s mobile commerce is headed in the same direction. The biggest reason for this accelerated development is the fact that Southeast Asia is truly a mobile-first market. Back in 2008, most, if not all, of China e-commerce was done via desktop or laptop computing.

By contrast, for many consumers in Southeast Asia the smartphone is the first and only foray into Internet and e-commerce. According to a Google study, in China 8 percent of users only access the Internet via a smartphone whereas this number is 31 percent and 21 percent in Malaysia and Vietnam.

We’ve already seen glimpses of the potential of mobile commerce in SEA as there’s a huge shadow e-commerce market, with transactions happening on Instagram, Facebook and Line. Also, Line has experimented and achieved success with mobile commerce initiatives such asLine Flash Sale and Line Groceries.

- An open vs. closed system & the hidden potential of social media “shadow markets”

China is a closed system. In the past, the Great Wall of China kept invaders out of the middle kingdom. Today, the “Great Firewall of China” keeps out foreign Internet and e-commerce companies, with notable victims like eBay, Google, Groupon, and Amazon. SEA is an open system with porous borders. As a result, SEA’s ease of foreign entry will lead to hyper-competition.

While banned in China, Instagram, Facebook and Line are the most popular social media platforms in SEA. Their popularity combined with local entrepreneurship and ingenuity has resulted in these platforms informally being used for e-commerce.

In Thailand alone, GMV on social media sites like Instagram and Facebook was estimated at $510m in 2014. This is a solid one third of total e-commerce GMV in Thailand (official reported GMV excluding ‘shadow markets’ contribution was $0.9b in 2013). Because of their dominance and reach, these platforms should be considered as serious competitors to anyone looking to disrupt the e-commerce marketplace game in Southeast Asia.